If the definition of heaven is a strange but comforting melody telling stories of the timelessness of the human soul, then one corner to find it is in Indonesia’s southernmost inhabited island; Roté.

Located just a 2-4 hour sail southwest of its more famous neighbour Timor, Roté is a 70-km long arid island covered in savannahs and sugar palms (Borassusflabellifer, locally known as tua or lontar). Lontar is central to life in Roté; as a source of food, fibres for weaving, wood for construction, and music.

Alas, on my trip to Timor, I didn’t make it to Roté due to marine hazards and cancelled ferries. Fortunately, there is a place in Timor that makes me feel one step closer to Roté; the sasando workshop of Jeremias Pah in Oëbelo, 22 kilometres east of Kupang.

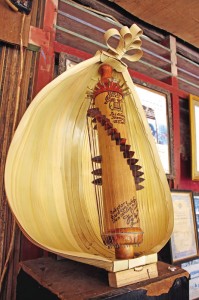

Sasandu, a pentatonic harp made of a bamboo core, bamboo or metal strings, movable tuning bridges, and a robust palm-leaf resonator, is a native instrument of Roté. For generations, the Pah clan has been known as guardians of the Rotinese musical heritage and developers of sasandu’s modern diatonic daughter, the sasando biola.

Sasando gained recent national attention in 2009 when jazz composer Dwiki Dharmawan included it in a performance before President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and then-Minister of Culture and Tourism Jero Wacik. The President then called for a sasando competition in Kupang, which attracted 358 out of the 400 known existing sasando players.

Upon my arrival, Pah appeared in the traditional outfit; white shirt, dark woven selimut with a matching scarf, and the ti’Ilangga palm sombrero. With a palm harp on his lap, the 75-year-old maestro sat down before his savvy laptop and recording equipment, and started playing Batu Matia – a traditional melody that no two musicians I’ve heard of plays the same.

The music is nothing like Java-Bali’s gamelan or angklung bambu. The traditional acoustic sasandu sounds clean and crisp like the banjo, but with a pentatonic tuning played to the rhythm of one’s heartbeat. There was unpretentious simplicity in melody, harmony, and facial expression. Pah sang with the soul of a wise storyteller.

According to the unpublished thesis of Dr. Christopher Basile, based on interviews with four senior sasandu maestros from the 1990s, the original sasandu was invented by Sangguana, a 17th century Rotinese fisherman who got shipwrecked and imprisoned in Ndana (Indonesia’s point-zero southernmost island, now uninhabited). Despite Basile’s claim of Sangguana’s historical accuracy, Pah does not endorse this story.

The Princess of Ndana fell in love with Sangguana and assigned him to invent music that has never existed before. With inspiration from a desperate dream, Sangguana created a sandu (Rotinese: “tremble”) from a length of bamboo, seven strings from banyan roots, and a resonator from the robust palm leaf. Over daily music lessons, Princess and Sangguana began a scandalous love affair that triggered chaos in Ndana and had Sangguana killed.

The news reached Sangguana’s wife in Roté, who was pregnant with their son Nalesanggu when Sangguana left years ago. When Nalesanggu came of age, his mother told him of his father’s tragic fate. In revenge, Nalesanggu massacred every single person on Ndana, including the Princess for whom the sasandu was invented. Nalesanggu then brought the sasandu back to Roté and taught it to the Rotinese in honour of his father.

The sasandu then evolved into the sasando biola in the early 20th century when Roté became increasingly Christian and adapted Dutch customs, music, and dance. Ougust Pah and Edu Pah, the father and uncle of Jeremias Pah respectively, have been credited among the early developers of sasando biola.

Pah started learning sasando as a child in the 1940s-50s playing hymns in church. In 1962, he moved to Kupang in order to develop the modern sasando and give it greater exposure to other Indonesians and foreigners. As a devout Christian, Pah credits his family’s ongoing legacy of sasando to divine inspiration.

“Because of the resonator, the sasando used to be difficult to carry around”, said Pah. One Sunday morning, the arrival of an unannounced guest delayed Pah’s plan to attend church. “I arrived in the middle of a sermon and took the only seat left next to some ladies. It was hot, so a lady pulled out a folding fan from her purse. It was as though God was telling me to develop a foldable resonator similar to the lady’s fan.”

Pah said he had no difficulties passing on the musical tradition to his ten children. At least four of Pah’s grown sons currently make a full time living performing, making, and teaching sasando.

“Passing on a tradition to one’s children shouldn’t be difficult. A non-Rotinese student of mine learned three songs on the sasando in just four days”, said Pah. “Where there is a will, there is a way. The key is to start your children early in growing a genuine love and interest in the music.”

Pah then called his youngest, 10-year-old Rino, to play Bolelebo on the electric sasando. For a young learner, Rino’s performance already sounded well-structured and practiced. Smiling proudly at his son, Pah hummed along to the tune and told me that Rino will be performing in Singapore in December.

“Oh no, I played that part wrong”, the boy gave a shy giggle as he finished the song, before running back into the house.

In 2010, Pah’s sons Djitron and Berto were contestants in two separate nationally televised Indonesian talent shows. Each performing the electric sasando biola, their repertoires included Jason Mraz’s I’m Yours, Il Divo’s I Believe in You, Richard Clayderman’s Ballade Pour Adeline, and Padi’s Begitu Indah.

Among the many tunes Pah has performed on the sasandu and sasando biola, Pah sums up the soul of his music in three songs: Lelendo (“Battle Song”), Te’o Renda (“Embroidering Woman”), and Batu Matia (“Heavy Rock”).

Lelendo is a song of the bloodshed the sons of Roté fought for the sovereignty of Indonesia during colonial times. Te’o Renda is a song about a time of peace after the war, when women rise hours before dawn to make embroidery, as if embroidering a bright future for the dawn of a new generation. Batu Matia is a song about a young man who asks for the embroidering woman’s hand in marriage, committing to build a steadfast immovable love like a heavy rock as they tackle life’s hard realities together.

As the maestro watches his children develop their generation’s version of the ancient palm harp of Roté, Pah continues to brim with timeless memories of the music he’s lived for. And those who have had the privilege of meeting him would likewise come home brimming with memories of melodies from Indonesia’s Far South.

Jeremias Pah Sasando Workshop

Jl. Timor Raya Km 22

Desa Oebelo

Kecamatan Kupang Tengah

Kabupaten Kupang

Nusa Tenggara Timur

Indonesia