Gambling, like prostitution and corruption, is an age-old vice that is part of Indonesia’s culture.

Despite being criminalized in the 1970s, the gaming industry is flourishing, thanks to protection from crooked politicians, military officers and police receiving a cut of the profits.

From maids buying Rp.1,000 black market lottery tickets, to Balinese betting passionately on cockfighting, to tycoons staking thousands of dollars on a roulette wheel spin, gambling appeals to a broad cross-section of Indonesians, although most are wise enough not to squander their money on illegal games of chance.

Opponents of gambling argue that it can cause financial ruin, divorce and moral decay. Supporters claim the government could be earning at least $1 billion a year to fund public infrastructure if gambling was regulated and taxed. Neighbouring Singapore is forecast to earn $6.4 billion from its two casinos this year, putting it on par with Las Vegas.

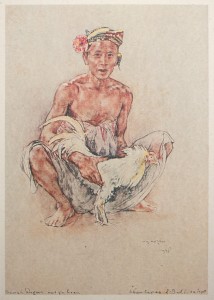

The earliest forms of gambling in Java predate the arrival of the Dutch, Islam and the Chinese. Any two animals or insects that could be put together to fight were fair game for betting. Cockfighting remains popular and is semi-legal in Bali, provided that it takes place during religious ceremonies, as the roosters can be deemed sacrifices whose blood will cleanse the earth. Some of the money staked on these occasions goes to traditional village councils.

One of the most bloodthirsty betting spectacles in Java involved pitting a buffalo against a tiger. Buffaloes are usually docile and the now extinct Javanese tiger tended to be shy of larger animals, so the beasts would have to be put in the mood for fighting. This was achieved by anointing the buffalo’s flanks with a paste of nettles and chilli, while the tiger would be goaded with fire and boiling water. Buffaloes were usually victorious in these bouts, which took place in bamboo enclosures, but any triumphant tiger would subsequently be speared to death. By the colonial era, this bias was said to be because the buffalo symbolised the Javanese, while the tiger represented the Europeans.

Other early gambling centred on boat races and kite fighting, the latter involving bringing down an opponent’s kite in mid-air. Also popular was betting on which nut might crush an opponent’s nut. Another simple game involved betting on the number of seeds held in the hands of two or more people.

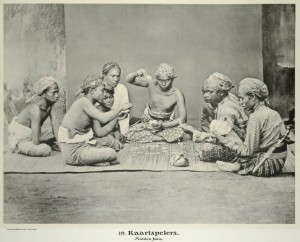

Chinese migrants, who first arrived about 700 years ago, introduced new types of gambling, especially card and coin games. Gambling was popular at weddings and public events, but with the rise of Islam in the 1500s, it was later banned by some sultans and rajas, although other rulers were risking entire fortunes, palaces and wives on games of chance.

Under Dutch rule, various forms of gambling were permitted because they provided the colonial administration with considerable revenue. The Dutch-run lottery was taxed at 21%, with 20% going to the government and 1% to the poor. Contract labourers were often kept indentured because of their addiction to gambling and opium. When the British took over much of the Dutch East Indies from 1811-16 most gambling was banned by the new governor, Thomas Stamford Raffles, although he did establish a lottery to fund a road on the northern coast of Java. Some of the British residents of Batavia founded a horse racing club, which although discontinued after a few years, inspired racing clubs throughout much of Java. The Dutch re-legalised gambling when they returned to power in the Indies, although they did eventually ban cockfighting in 1926 after an inquiry into the negative impacts of gaming.

After Indonesia achieved independence, the central government in 1957 allowed provincial administrations to regulate gambling for

their local revenue, but many were reluctant to do so because of criticism from Muslim leaders. It was not until 1967 that gambling was legalised in Jakarta by Governor Ali Sadikin. The industry was tightly controlled with the aim of ensuring the money flowed to municipal coffers and that locals did not become impoverished gambling addicts. Licenses were awarded by tender to establish three casinos: Petak Sembilan on the 13th floor of the Sarinah building, Copacabana at Hotel Horison in Ancol, and the New International Amusement Centre in the old Jakarta Theatre complex. Gambling centres with slot machines were also allowed in several areas. Greyhound racing was introduced at Senayan Stadium. Horse racing commenced at Pulo Mas, East Jakarta, with eight races being held every Sunday. The race course was funded with about $5 million from Australian investors, who also sent over horses and jockeys for the first races. The horses were held up in quarantine for a week, so by the time of the first meeting, several of the Australian jockeys had contracted venereal disease and endured a painful race day.

Sadikin established two lottery systems, which were also introduced in other provinces and ostensibly used to raise funds for sporting events. Within a decade, Jakarta’s development budget has increased tenfold, enabling the governor to build schools, medical clinics, roads and markets. Mounting criticism from Muslim leaders prompted the government in 1973 to issue a ministerial decree banning public gambling practices. In 1974, a tougher law was issued, revoking all gambling permits, but Jakarta’s casinos continued to operate, technically being open only to foreigners. After Sadikin fell out of favour with President Suharto, the government in 1981 issued a regulation banning all forms of gambling throughout the country.

Legal gambling re-emerged in December 1985, with soccer pools called Porkas, set up to raise funds for the development of the sport. In response to Muslim protests, Porkas was renamed twice in efforts to sound more respectable, but it was axed in 1989 amid concerns that villagers were squandering their savings. The lottery was next reincarnated under the name of Social Fund Donation Prizes (SDSB), which was prohibited in 1993 following an increase in the number of Muslims in the national parliament.

The gambling bans did not spell an end for the Pulo Mas race track. The Indonesian Horse Sports Association continues to organise race days, one of the more recent being the Kapolri Cup-Jakarta Derby, held in association with the National Police. As for the casino operators, many of them simply went underground, forming what became known as the untouchable Nine Dragons Network, which now has a new generation of leaders, operating about 44 gambling locations in Jakarta alone. Several other major cities have covert gambling centres, some with big casinos, others simply with rows of slot machines, known locally as ‘Mickey Mouse’ machines because many feature the Disney icon or other cartoon characters, such as Bugs Bunny.

One side effect of the closure of Jakarta’s three licensed casinos was the opening of a casino on Australia’s Christmas Island in late 1993. Funded mostly by Indonesians and some Australians, the casino was only an hour’s flight from Jakarta on the Suharto family’s Merpati Airlines. After a healthy start, the casino was hit by the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, its license was suspended by the Australian government and it never reopened.

Numerous proposals for controlled, legalised gambling have failed over the past decade, officially because of opposition from Islamic groups, although there may be reluctance from those currently controlling and protecting the industry to lose any of their profits. Sources say tributes are also paid to youth and civic organisations to ensure they never complain.

Under the law, gamblers face a maximum sentence of 10 years in jail or a fine of up to Rp.25 million. Law enforcers tend to ignore the big fish and instead prey on the smallest offenders. Former President Gus Dur in 2000 ordered the arrest of the country’s most notorious gambling kingpin but police and public prosecutors refused to act, claiming there was insufficient evidence. Police in 2009 showed their mettle by arresting 10 shoe-shine boys, aged between 8 and 15, for placing Rp.1,000 bets in a coin-toss game in a car park at Soekarno-Hatta Airport. The children were sent to court and convicted. In Aceh, which has a long tradition of horse racing, people caught gambling for small sums of money are routinely rounded up and publicly flogged. Not far away on the resort island of Batam, which has long catered to Singaporeans seeking sex and gambling, proposals to legalise casinos and gaming areas have been rebuffed. On the other side of the archipelago, in Papua, police this year shot dead a vendor of illegal lottery tickets allegedly because he was not sharing his profits.

In 2010, a vegetable vendor in Jakarta, jailed for betting Rp.58,000 in a card game, joined forces with an ethnic Chinese man to file an unsuccessful judicial review against the 1974 law banning gambling. They argued that a state law should not be used to enforce the Islamic prohibition of gambling, adding that betting was part of their culture and that non-Muslims should not be victimised.

Some of the more obvious forms of gambling today include arisan – a private revolving lottery, in which everyone eventually wins, and late-night motorbike drag racing, in which youths use relatively empty streets as racetracks for their brief, moth-like lives. Golf courses are another common location for gambling. Websites offering gambling draw plenty of punters. Also popular is gambling on football, with many local bookies taking bets on domestic and international games. The government is considering classifying gambling on sport as a form of corruption, which would mean harsher penalties for offenders. For poor people dreaming of buying a motorbike or a house by winning a black market lottery, gambling could become more risky; whereas the highest rollers and their hosts have little to fear with the deck remaining stacked in their favour.

Also Read Robby Sumampow, Indo Kordsa Entrepreneur and Owner Dies