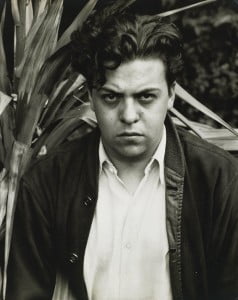

Miguel Covarrubias’ father was a Sunday painter. As a very young child, Miguel liked to sit by his father, watching him work. This happened nearly every weekend. Noticing his interest, his father gave the little boy paper and pencil. Miguel now happily occupied himself making pictures. As he grew, the sketches were calling attention to his burgeoning facility to draw. By the time he was fourteen years old and in high school, he was making caricatures of the teachers to the amusement of his classmates.

Miguel Covarrubias’ father was a Sunday painter. As a very young child, Miguel liked to sit by his father, watching him work. This happened nearly every weekend. Noticing his interest, his father gave the little boy paper and pencil. Miguel now happily occupied himself making pictures. As he grew, the sketches were calling attention to his burgeoning facility to draw. By the time he was fourteen years old and in high school, he was making caricatures of the teachers to the amusement of his classmates.

From then on, wherever Covarrubias went, he carried with him a pencil and sketch pad at the ready to put to paper someone or something that caught his attention. In the evenings, he liked going to vaudeville revues and, later, to the cafés where Mexico City’s intellectuals and artists gathered.

Covarrubias is remembered from that period as a shy, chubby boy sitting in a corner always busy drawing. He was given the affectionate nickname of “El Chamaco”, “The Kid”, a pet name that would stay with him for the rest of his life. Some of the caricatures he made of already well-known artists, such as Diego Rivera or the visiting writer, D.H. Lawrence, ended up pinned to the walls of “EL Monote”, one of the cafes. Soon he was asked to contribute caricature Mexico City’s fashionable magazines and to student publications, including the popular art journal Zig-Zag.

By the time he was eighteen, Covarrubias found himself in New York City and was soon making caricatures of personalities from the art and entertainment world, and celebrities from the political and social worlds. He also became an important contributor to the Harlem Renaissance movement. Alan Fern, a former director of the Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. wrote, <Covarrubias> “seems to us the quintessential commentator of American life in the 1920s”.

By the time he was eighteen, Covarrubias found himself in New York City and was soon making caricatures of personalities from the art and entertainment world, and celebrities from the political and social worlds. He also became an important contributor to the Harlem Renaissance movement. Alan Fern, a former director of the Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. wrote, <Covarrubias> “seems to us the quintessential commentator of American life in the 1920s”.

Al Hirschfield, who shared a studio with Miguel in the twenties commented, “I know he use to diddle a lot and sketch on tablecloths and menus in restaurants …. In Harlem he made hundreds of sketches in a sketchbook and, when there were no longer any blank sheets, on match boxes, on napkins, and on anything else he could find.”

After the publication of Covarrubias’ first book in 1925, The Prince of Wales and Other Americans, his mentor Carl Van Vechten marvelled, “I have always held it as an axiom that a caricaturist should know his subject for ten years before he sat down to draw him….<But Covarrubias> has relieved me of that superstition. Ten minutes with any of them was all he required. The result was not superficial… <The subjects> are all set down so vividly that posterity might study them to better advantage in the art of Covarrubias than through written criticism of their work.”

Later that year, Van Vechten once again made a similar observation in his novel, Firecrackers, which he dedicated to MC. In the book, a character muses about “a young Mexican boy, Miguel Covarrubias, who created caricatures of celebrities who he knew only by sight and name, which exposed the whole secret of the subject’s personalities. Here was clairvoyance.”

Beginning in 1926, Covarrubias began illustrating books. As he read the text he would start sketching and, in the end, choose the most fitting images. Some of the drawings were repeated as many as fifteen times in a patient experimentation to find the right approach and technique.

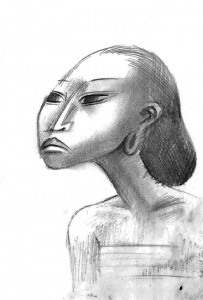

Covarrubias book, Negro Drawings was published two years later. In his preface to the book, the caricaturist, Ralph Barton attested “Covarrubias’s drawings…need merely to be looked at to be understood. To draw as Covarrubias draws, one has only to be born with a taste for understanding everything. As we look at the drawings we are aware that they bear the stamp of genius.” After its publication, the Encyclopedia Britannica listed him among the “wonders” of black-and-white artists.

Covarrubias book, Negro Drawings was published two years later. In his preface to the book, the caricaturist, Ralph Barton attested “Covarrubias’s drawings…need merely to be looked at to be understood. To draw as Covarrubias draws, one has only to be born with a taste for understanding everything. As we look at the drawings we are aware that they bear the stamp of genius.” After its publication, the Encyclopedia Britannica listed him among the “wonders” of black-and-white artists.

In 1928, the Valentine Gallery in New York City gave Covarrubias his first exhibition. The catalogue stated, “The simplification that is such an important element in the Covarrubias drawings is seldom attained. He begins a picture after no more than the most summary of thumbnail sketches, but he is willing to draw and redraw until his acute sense of pictorial rightness is satisfied. The final result is usually deceptively simple. It has a look of immediate and spontaneous creation.”

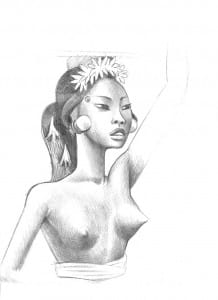

Covarrubias married Rosa Rolanda in 1930. For their honeymoon they travelled by ship to China and on to Bali. Covarrubias threw himself into Balinese life. Everything he witnessed was recorded in sketches. The result of his two sojourns in Bali was his book, Island of Bali, published in 1937. Many of the subjects in the book are illustrated by a summary sketches.

Covarrubias became a passionate anthropological researcher. He immersed himself in the arts and culture of primitive cultures. His manner of sorting out ideas and the way of his understanding a culture was through the use of drawing. As a teacher, his students remember him with the always present pens in his coat pocket and a notebook to make sketches. In the classroom to illustrate what he was describing, Covarrubias would simply turn to the blackboard and draw. “It goes something like this….”

The same was true for his archaeological research. The Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso stated, “He gave to archaeology something that it lacked….and that was an aesthetic perception of form, always correct.” The archaeologist, Michael Coe stated, “I learned much from his drawings.”

The same was true for his archaeological research. The Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso stated, “He gave to archaeology something that it lacked….and that was an aesthetic perception of form, always correct.” The archaeologist, Michael Coe stated, “I learned much from his drawings.”

The group of Bali and Chinese sketches in this exhibition executed by Miguel Covarrubias in the early thirties is a window into the creative process of his manner of working. Wherever he was, he recorded people and events for later use. These sketches show his keen powers of observation and his intellectual curiosity and his faithfulness and artistic understanding of his subjects.

Many of these preliminary drawings were the first step prior to developing into refined line or wash drawings or studies in colour. Good examples from the Bali sketches are the corresponding final works “Food Stall”, “Every Night is Festival Night”, “Brahmin Priest or Pendanda” and “Princess and Attendant” (A scene from the Ardja, Balinese Opera). These works can be viewed in Covarrubias in Bali published by Editions Didier Millet. From the Chinese sketches, there are several enhanced drawings for Marc Chadourne’s book China and a gouache for the jacket of Albert Gervais book Madame Flowery Sentiment in 1937.

Miguel Covarrubias began his career as a caricaturist and graphic artist. Whether he was working on a caricature, a book illustration, teaching a course, designing a map or sets for a ballet, studying a culture or solving an archaeological mystery, he always sketched.

The sketches in this exhibition are examples of the way he worked and are art objects in their own right. Rubin de la Borbollas said, “Perhaps one of the most profound lessons to be learned from Covarrubias was there is no aspect, however abstract it may be, of human knowledge or nature that surrounds man which cannot have and should not have a graphic interpretation.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

i) Miguel Covarrubias Caricatures, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C. 1985, p.12ii) Ibid. p.20

iii) Hirschfeld, Al, Interview with Adriana Williams, New York City, 1985.

iv) Van Vechten, Carl, The Reviewer, Vol.4, 1923-4, (New York: Johnson Reprint Company, 1967): 103.

v) Van Vechten, Carl, Firecrackers, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1925):127-128.

vi) Barton, Ralph, Preface to Negro Drawings by Miguel Covarrubias, (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1927).

vii) British Encyclopedia Britannica, 2oth edition, s.v. “Caricature”.

viii) Valentine Gallery Catalogue: (New York City, 1928).

ix) Romano, Arturo, (Mexican archeologist): Interview with Adriana Williams, Mexico City, July 1987.

x) Caso, Alfonso, Interview with Elena Poniatoska, Novedades, Mexico City, May 1957.

xi) Coe, Michael, (American archeologist) Telephone interview with Adriana Williams, November 1991.

xii) Rubín de la Borbollla, Boletín Bibliográfica de Antropología Americana, (Mexico City: Instituto de Geografía e Historía), p.138.