Before moving to Indonesia in the mid-1990s, I lived in a grim London suburb called Kensal Green, where counterfeit money was plentiful. A fake £20 note could be purchased for just £5. Apparently, the preferred method of getting rid of them was to target a busy McDonald’s, get in line for the till operated by the youngest cashier and order the cheapest thing on the menu. Villains could cover five fast-food places in an hour, converting £25 of phony money into £95 pounds of real money and some unhealthy snacks. Never keen on living among criminals, I moved to India and then Indonesia.

When the Asian financial crisis struck Indonesia in mid-1997, one of my biggest concerns was that my salary was being paid into Bank Andromeda, partly owned by Suharto’s middle son, Bambang Trihatmodjo. The bank was liquidated, along with some of my savings, in November 1997. Unfazed, Bambang simply took over another bank, which was also soon liquidated in line with reforms imposed by the International Monetary Fund.

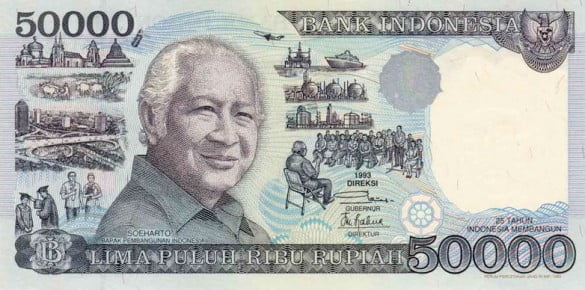

In 1999, after the Rupiah had irretrievably plunged, counterfeit Rp.50,000 notes began entering circulation and amounted to at least Rp.29 billion ($2.6 million) by February 2000. These notes featured Suharto’s portrait, ironically captioned Bapak Pembangunan (Father of Development).

Anti-corruption activist George Aditjondro, in his deftly titled 2006 book Presidential Corruption: Reproductive Oligarchy Tripod: Palace, Barracks and Ruling Party, states that a police investigation into the counterfeiting led to the military and the Suharto clan. The wife of Suharto’s grandson was caught using fake money at a Jakarta hotel, while a printing press used to make the money was suspected to be owned by one of Suharto’s children. Aditjondro offers no hard evidence to back up the latter assertion. He also alleges that Bambang Trihatmodjo’s company, PT Tridaya Esta, cooperated with a state enterprise to produce paper sold to the state mint, Peruri.

Counterfeit rupiah were used in the period surrounding East Timor’s 1999 independence referendum, during which about 1,400 people were murdered. Desperate to retain the territory as its private stomping ground, the Indonesian military formed local militia proxies, which were tasked to terrorize the East Timorese into voting to stay with Indonesia. These militias were paid in counterfeit. There is a story that one of the most prominent militia leaders took some boxes of money across the border into West Timor and tried to deposit them into his bank account, only to be informed the cash was forged. When he complained to an Indonesian Military intelligence general, he was castigated for being so stupid as to embezzle fake money intended for the killing squads.

Details of this operation came to light in Jakarta in 2000, when two former soldiers, Ismail Putra and Eddy Kereh, were tried and jailed for counterfeiting. Ismail said that then-Army chief General Tyasno Sudarto, who previously headed the Military’s Intelligence Agency, had instructed the syndicate to print the money to pay for the militias. He said Tyasno told him the order had come from General Wiranto. Prosecutors and judges refused to summon Tyasno, who told the media the allegation was slander.

A police witness at the trial, Umar Faroq, said records showed the syndicate paid Rp.10 million to the state mint for providing them with negatives for the banknotes. He also said the Defence Ministry provided serial numbers for the money. The first batch of notes, amounting to Rp.19.2 billion, were printed in September 1999 and ordered destroyed because they were too low in quality, but some of them ended up in circulation in Jakarta.

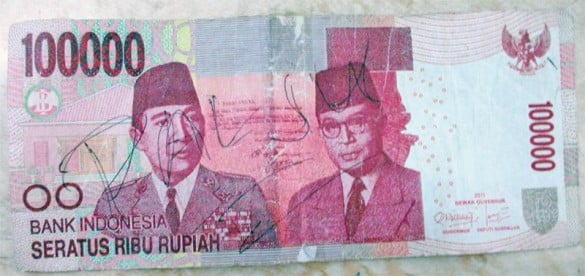

The Suharto banknotes were withdrawn from circulation in 1999 and an Australian firm was contracted to print new denomination Rp.100,000 polymer notes for Indonesia. By 2004, these were replaced with the red 100,000 notes featuring founding fathers Sukarno and Hatta.

Advances in computer technology and printing are making it easier to forge money. One of the hardest details to fake on current Indonesian currency is the ‘patch’ that appears on the lower right corner on the face of the 100,000, 50,000 and 20,000 notes. At a glance, these patches appear dull, but they are reflective or change colour when tilted under intense light. Paper quality is also often a giveaway, as the high denomination notes are printed on imported European paper, while local paper is used for the Rp.5,000 and lower notes. The central bank says less than 0.01% of the rupiah in circulation are counterfeit.