To know the lie of the land is an essential ingredient for travellers, and for anyone dealing with land tenure, or the management and use of the land’s natural resources. This is especially true in respect of the confusing and conflicting land ownership rights of Indonesia’s indigenous peoples.

In 2012, the Constitutional Court declared that customary (adat) forests no longer belong to the state. This follows the Court’s decision No. 41/1999 on forestry, which recognized the presence of customary forests. The decisions are unfortunately a tad late as the Basic Agrarian Law No. 5 of 1960 capped private land ownership in rural areas and declared all unclaimed land to be state-owned.

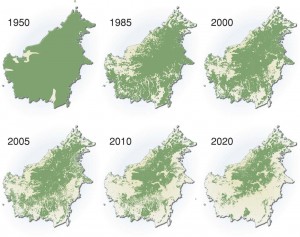

The ensuing flood of logging licenses and permits to convert forests to agro-estates, industrial forest plantations and strip mining drastically changed the land-use and vegetation cover, especially in Sumatra, Kalimantan and Papua, and dramatically reduced the size of the adat land.

As a result, national income increased and a small group of investors were able to significantly increase their wealth, but the losers were the indigenous forest dwellers who, as hunter-gatherers, rely on extensive forests and a healthy ecosystem for their livelihood.

This situation is ongoing, as an article of 7 March 2015 in The Jakarta Post illustrates: “The tribal community leader of the nomadic Orang Rimba in Jambi, Temenggung Marituha, has blamed forest conversion as the cause of the food shortage they are currently suffering that has led to the deaths of 11 tribespeople from starvation.”

Even more disturbingly, this group of 73 families is suffering from a lack of clean water. They live in the Bukit Dua Belas National Park in the Barisan Mountains, but their water sources have been polluted. As there are no industries in this protected forest, this could only be caused by (illegal) mining or (illegal) logging—the former uses cyanide and mercury, and the latter chromated copper arsenate.

Even more disturbingly, this group of 73 families is suffering from a lack of clean water. They live in the Bukit Dua Belas National Park in the Barisan Mountains, but their water sources have been polluted. As there are no industries in this protected forest, this could only be caused by (illegal) mining or (illegal) logging—the former uses cyanide and mercury, and the latter chromated copper arsenate.

As always, the implementation of decisions by government authorities is slow and faltering. In respect of customary land, this is unfortunately also true, as the authorities at district, provincial and national levels are not sure how to proceed. But, as the adat lands have now been put on the map, so to speak, the process of regulating the adat land tenure could be given a leg-up by starting to map these lands soonest.

According to the Nusantara Traditional Community Alliance (AMAN), some 33 million hectares of customary land, or 17% of Indonesia’s total land area of 190 million hectares, need to be mapped. Some 17 million people from more than 2,000 traditional communities will directly benefit from the mapping exercise, as it would assist in resolving land disputes.

Quite obviously, the Kalimantan wall-to-wall forests of 1950 are no more, and their disappearance has drastically reduced the livelihood of the many indigenous groups on the island. It will not be possible to restore the forests to the conditions of 50 years ago. However, fixing the tenure rights to the remaining forests, the oil palm plantations, the clear-felled areas and the mining concession areas would solve many problems, uncertainties and frustrations.

The first step on this [long] road will be the mapping of the customary domains where conflicts occur, with the balance mapped subsequently. It is not immediately clear to what extent customary land that has already been converted to other uses should be included in the mapping process. The most practical approach might be to map first and then decide what to do with the information.

Mapping the adat lands would need to be done accurately and linked to the national references. The maps must show standard themes, such as land use and vegetation cover, together with those that are relevant from the point of view of the indigenous communities. To achieve that, the mapping will need to be done by the communities themselves, assisted where necessary by public or private bodies.

The 121 inhabitants of Punan Adiu, a village in Malinau district, North Kalimantan, resorted to participatory mapping to protect the customary forests, which comprises more than 17,000 hectares of primary tropical rain forest.

The mapping took three years and included surveys and negotiations to establish the borders with other villages and the boundaries of the adat forest. The final map was completed in January this year, and must be approved by the district head of Malinau. Punan Adiu collaborated with a number of organisations, among others the Community Mapping Network (JKPP) and AMAN, in carrying out the activities.

Outside interests have turned up and offered a large amount of money for the forest, the plan being to clear-fell and plant oil palm. The villagers of Punan Adiu have refused the offer, but some of the neighbouring villages did accept. We can only hope that more villages will refuse the offers, as it is high time to stop the degradation resulting from these deals.

Forest loss leading to monoculture, oil palm estates

While the approval of the district head is certainly needed in the division of tenure, one would hope that authorities at provincial and national levels would also be involved, as the map must be referenced to the national geospatial database. In this respect, the Geospatial Information Agency (BIG) should play a vital role in integrating the participatory maps into the national system of spatial information.

Until now the main impediment to finding a solution to the ubiquitous land disputes is a lack of reliable and accurate maps. The ones currently used at national, provincial or district level differ widely and customary land typically does not appear on any of them.

Participatory mapping in rural areas would be best complemented with a similar undertaking in urban surroundings. Google uses this system of crowd-sourcing globally with good results, and several trials have been made in Indonesia, too. Participatory urban mapping would, for instance, be very useful in identifying weaknesses in the drainage infrastructure. Based on the resulting maps, the responsibility for cleaning, maintenance and repairs could then be allocated to either the local neighbourhood, or the government’s annual operations and maintenance budgets. The latter is a prerequisite for successfully undertaking the former—without dredging the main rivers, for example, there is little enthusiasm or use in keeping the roadside drains clean.

And most importantly from the point of view of cartography—and this is where BIG should come in—a system of guidance, technical reviews and tests should be set up to ensure that crowd-sourced and other participatory maps will be based on Indonesia’s set of references, so that these can be coherently integrated with the national topographic maps.