Robin Marinos is living proof that one person can change the environment for the better, although his campaign to protect Indonesia’s marine life has nearly cost him his life on more than one occasion. Death threats from the military and being doused with petrol are among the perils he has faced.

Robin, who is of European and American parentage, began his Indonesian conservation work by chance during a 1997 diving holiday when he discovered massive trap nets in the Lembeh Strait – a major fish migration route off northeast Sulawesi. Hundreds of dolphins, whales, manta rays and other protected species were being killed, while traditional fishermen saw their catches reduced by up to 80%. The nets had been illegally installed by a company run by a Taiwanese seafood firm and local partners, including two retired generals and an active military colonel. Provincial and district officials were also involved. Robin filmed the hauling of a catch and the slow killing of a whale shark. He then brought the issue to international attention through the media and most memorably at the Asia Dive Expo in Singapore, where former Navy Chief Admiral Sudomo was promoting dive tourism in Indonesia. Robin gained several influential allies, including Sudomo, who was then chairman of the Suharto regime’s top advisory council. In the face of mounting pressure, the government eventually denounced trap net fishing and expelled the Taiwanese company. Large trap nets were subsequently banned worldwide.

During the campaign, Robin was informed that some military intelligence thugs had been sent to Sulawesi “to get rid of that American terrorist”. They forced a local newspaper editor to retract an article condemning the trap nets and demanded to know Robin’s whereabouts. He avoided detection by constantly moving one step ahead and being sheltered by local friends. The danger only inspired him to devote his energy to defending the defenceless, whether marine life or coastal dwellers unable to stand up to corrupt authorities. At that time, some of Indonesia’s conservation organisations seemed too busy to handle new cases, while others had become passive due to continual disappointments. Robin started his own organisation, Earth Advocates (www.earth-advocates.org), which was able to forge partnerships with local groups and concerned individuals.

To fund his activities, Robin designs and sells beachwear in Spain, visiting Indonesia whenever time and finances permit. Earth Advocates also relies to a lesser extent on donations. Unlike some high-profile conservation groups that spend big on administration, salaries and fund-raising, Earth Advocates spends nearly all of its funds on direct action that gets results. Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) President Carter S. Roberts receives an annual salary of over $465,000, while Robin does not earn any money for his conservation work.

After the trap nets, Robin turned his attention to Bali, where he successfully campaigned to stop the illegal construction of buildings on beaches. While there, he discovered that tons of garbage buried beneath the sand had been uncovered by swells and combined with bacterial run-off from rivers and streams to create bacterial bloom along Kuta Beach, resulting in dangerous levels of pollution. He published his findings, which were picked up and broadcast by CNN, prompting Bali’s administration to tighten waste disposal laws and remove industries from beaches. This helped to rehabilitate the waning sand crab population, although Bali’s waterways remain very polluted.

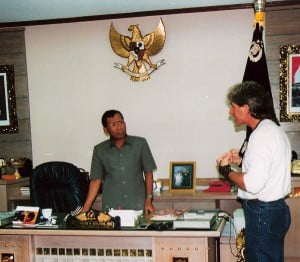

Robin was the first lobbyist to propose the resurrection of Indonesia’s Maritime Ministry, which had been axed in 1968 by Suharto, who was more focused on rice farming and kept fishing as a hobby. Robin argued the ministry was urgently needed, given that about 75% of the country’s territory is sea and requires streamlined management for conservation and sustainable exploitation. He had several meetings with an agency headed by then technology minister B.J. Habibie, who was later credited with reviving the ministry, which became a reality in 1999 under President Abdurrahman Wahid.

Robin was the first lobbyist to propose the resurrection of Indonesia’s Maritime Ministry, which had been axed in 1968 by Suharto, who was more focused on rice farming and kept fishing as a hobby. Robin argued the ministry was urgently needed, given that about 75% of the country’s territory is sea and requires streamlined management for conservation and sustainable exploitation. He had several meetings with an agency headed by then technology minister B.J. Habibie, who was later credited with reviving the ministry, which became a reality in 1999 under President Abdurrahman Wahid.

One of Robin’s greatest successes was saving green sea turtles from large-scale commercial slaughter in Bali. Under a 1990 decree, fishermen on the predominantly Hindu island could sell up to 5,000 turtles per year as sacrifices for religious rituals. The reality was that about 20,000 were being sold annually for human consumption – especially to Chinese restaurants across Indonesia, as well as for export to Singapore, Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong. At that time, the local WWF office was swallowing the lie that Bali’s turtle slaughters were a sacrosanct religious matter. Robin in 1998 brought a Balinese high priest to one of the main turtle slaughterhouses, where the starving, flipper-tied creatures were being butchered alive; their heads cut off only after all of the meat had been sliced away from the shells. The priest declared the slaughters to be sacrilegious and motivated by human greed. In 1999, Indonesian parliament passed a law placing the green sea turtle on the highly endangered species list. In 2000, Bali’s governor issued a decree prohibiting the trade of all endangered species.

Deemed responsible for the change in policy, Robin was attacked by two kingpins of the illegal trade, including Widji ‘Wewe’ Zakariah, who sprayed him with petrol during a turtle release ceremony and tried to incite a riot. Robin only intensified his lobbying, filed charges against Wewe and won the support of the provincial police chief. Authorities began raiding boats containing hundreds of turtles. Wewe then paid about 200 people to protest against the crackdown, threatening to attack local conservation officials, the governor’s office and to rape female WWF staff. In January 2001, a similar mob burned down the police station in Tanjung Benoa. Wewe was later sentenced to a year in jail and became a fugitive. In July 2001, Robin provided police with videotaped evidence of ongoing turtle slaughters, resulting in more raids and the release of over 260 dehydrated turtles.

Bali’s current governor I Made Mangku Pastika tried to reintroduce the turtle killing quota in 2009, in what conservationists viewed as a short-sighted act of treachery aimed at pleasing a few friends, but the move was rejected by the central government. Today, the illegal turtle trade continues due to some law enforcers turning a blind eye, but the scale of the slaughters is substantially lower than it was in the 1990s.

Earth Advocates’ other achievements include: successful lobbying for the Berau Marine Protected Area, which covers 1.27 million hectares in the Makassar Straits off East Kalimantan; stopping the construction of a luxury resort on Bunaken Island in North Sulawesi Marine Park; getting the whale shark classified as an internationally protected species; and enabling shark stocks to recover after winning protection for areas threatened by over-fishing.

Robin’s current priority is to stop a Chinese-funded firm from mining on Bangka Island off the coast of northern Sulawesi (not to be confused with Bangka-Belitung islands off Sumatra). Local fishermen and diving companies oppose the mining, fearing pollution will destroy their livelihoods. PT Mikro Metal Perdana has been granted a 2,000 hectare concession by North Minahasa Regent Sompie Singal, who is ignoring protests as well as the company’s violation of the 2009 Environment Law by its failure to conduct an environmental impact analysis. Locals claim the company is already shipping iron ore to China under the guise of “exploration”. The previous regent, Vonnie Anneke Panambunan, had backed Robin’s proposal for the creation of a North Minahasa Marine Protected Area but before it could be enacted she was embroiled in a corruption case and jailed. Her successor is yet to be convinced that it is worth protecting the island and its waters for the sake of sustainable fishing, marine eco-tourism and protecting rare fish species.

Robin’s current priority is to stop a Chinese-funded firm from mining on Bangka Island off the coast of northern Sulawesi (not to be confused with Bangka-Belitung islands off Sumatra). Local fishermen and diving companies oppose the mining, fearing pollution will destroy their livelihoods. PT Mikro Metal Perdana has been granted a 2,000 hectare concession by North Minahasa Regent Sompie Singal, who is ignoring protests as well as the company’s violation of the 2009 Environment Law by its failure to conduct an environmental impact analysis. Locals claim the company is already shipping iron ore to China under the guise of “exploration”. The previous regent, Vonnie Anneke Panambunan, had backed Robin’s proposal for the creation of a North Minahasa Marine Protected Area but before it could be enacted she was embroiled in a corruption case and jailed. Her successor is yet to be convinced that it is worth protecting the island and its waters for the sake of sustainable fishing, marine eco-tourism and protecting rare fish species.

Robin, who has degrees in psychology and business administration, is considering selling his clothing business by the end of this year so he can completely devote himself to environmental issues. International conferences and meetings with government officials take up a large part of his agenda but he prefers to be in the field, taking action.

One of his long-term goals is to save coral reefs from destructive fishing practices involving explosives and cyanide, by educating fishermen to adopt alternative income sources, such as farming sea cucumbers and seaweed. He also plans to lobby the government to reform the state education curriculum to include lessons on conservation and sustainable development. Another project is to improve Bali’s ecosystem by encouraging landowners to plant teak, fruit and flowering trees.

Robin modestly attributes his success to hard work, good friendships and good luck, but his associates say his tireless energy, enthusiasm, unselfishness and charm are what get results.