When it comes to ostentatious shows of wealth, no one does it better than the Europeans. Backed by generations of inherited riches, the elites of England, France and Germany would express their affluence the only way they knew how; building bigger, better, brasher country estates that screamed ‘look at me’ at their neighbours, peers and tenants.

Old money with its attachment to succession, wealth and right found it easy to build. Without pesky distractions like unions or health and safety, the rich were only constrained by their imagination, and as the European economies boomed, new money, in the shape of people who had made their fortune in ‘trade’ were only too keen to flaunt their new found wealth, often built on the back of trade in the colonies, including Indonesia.

For sheer extravagance perhaps very few can beat the eccentric, fairy tale castle built by Ludwig II of Bavaria in the second half of the 19th century before Germany became a distinct entity. Drawing inspiration from Teutonic tales of the Middle Ages, as well as the music of Wagner Neuschwanstein, combining elements of Romanesque, Gothic and Byzantine, all brought together on the ridge of a cliff to provide surely one of most dramatic pieces of real estate in the world.

In England Blenheim Palace boasts a tenuous link to Indonesia. It is the stately home of the Duke of Marlborough, a name that crops up on the west coast of Sumatra at Benteng Marlborough, a one-time staging post for the East India Company, while there is some suggestion that the famous street which runs through the heart of Yogyakarta, Marliboro, is a local adaptation of the name.

Built over 200 years ago, the house today typifies stately homes in 21st century England. It boasts a maze, adventure playground and a butterfly house, as well as the sumptuously appointed rooms and regular exhibitions and gardens; enough to keep people busy for a few hours after they have handed over their 21 GBP admission fee. And don’t forget the cafes and restaurants!

Indonesia, on the other hand, boasts three ‘national’ palaces (Istana Negara, Istana Bogor and Istana Cipanas), which are not always open to the public. The closest most people get is feeding the deer through the fence outside Istana Bogor. And that’s about it. The idea that an old building can be turned into an item of beauty that people would be willing to pay money to look at has yet to catch on, and the few that remain are jealously protected by their current owners.

The earliest wealthy burghers of what was known as Batavia would have been Dutch colonialists and as they moved beyond the city walls, one of the first places they settled upon was what we now know as Jalan Pangeran Jayakarta. The move south was held up as gangs of marauding natives and wild animals made living too far from the walls a dangerous option.

As the Dutch East Indies Company strengthened their hold on Batavia and trade, the area was made safer, however the rich, abhorred by the stagnant canal waters in the centre, moved away to find some peace and comfort. Areas like Jalan Gunung Sahari and Jalan Hayam Wuruk would have been regularly featured, had there been a 17th century magazine like Tatler.

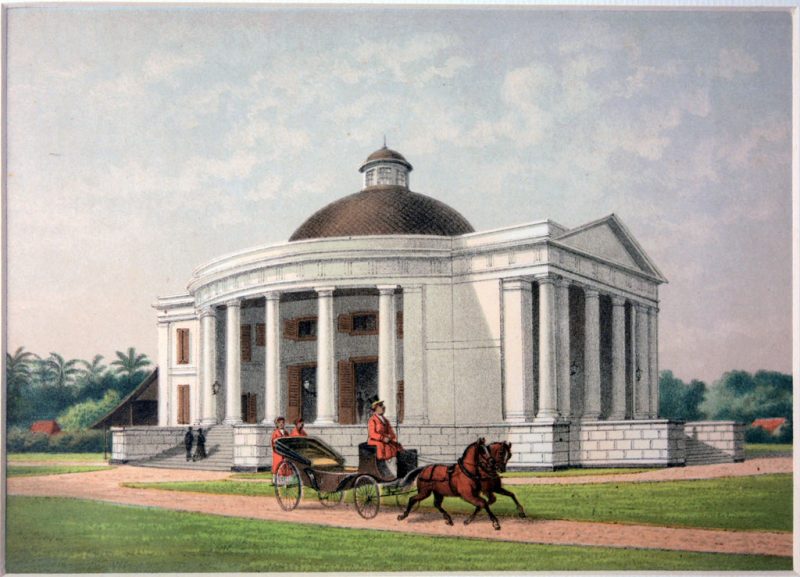

Lapangan Banteng, once the political and military heart of Batavia, still boasts a couple of examples of its one time grandeur. The current Department of Finance building (construction begun 1809) was initially designed for the Governor General, while the wings were for government officials. Nearby, the Supreme Court of Indonesia was constructed in 1848.

An English visitor, Charles Noble, reported in 1765: “The ground for about 10 or 12 miles around Batavia is pretty well cultivated. The gentlemen have their country houses, gardens and ponds after the Dutch mode”. This suggests a world of tranquillity and serenity, which he would find difficult to come across today.

An early French visitor, in 1810, described the area: “This promenade is one of the nicest you see, all side streets are ornated with beautiful palaces, residences of the members of the Council of the Indies, the main officials of the Company and also the richest merchants”.

When Governor General von Imhoff built a palace in Bogor, he sparked a real estate boom as other high officials and people with influence followed his lead south, but high costs saw them sold on and the idea of a heredity seat passed.

As outsiders, the Dutch were never likely to stay long and independence after World War II hastened their departure. Jakarta historian, A. Heuken, writes in his seminal ‘Historical Sites of Jakarta’, “Many of those still in good condition before World War II have been burned or destroyed in the turbulent years after 1945 in order to prevent former owners from returning to their estates”.

One example is worth considering. Pondok Gede, not far from the current Halim Airport, was built in 1775 by a Dutch Protestant minister. A long building with an enormous roof, it was built in a mixture of Indonesian and Dutch styles. Its importance was recognized when it was protected by law, but this didn’t stop a highly placed family demolishing it in the 1990s and replacing it with a supermarket.

Where the wealthy once led, the rest still follow. Jakarta’s expansion south carries apace, bringing interminable mall and housing estate construction, along with the occasional road to access these new areas. The new, home-grown elite build their country retreats on the slopes of Puncak and Gunung Salak with a focus on practicality over ostentatious; high walls and barbed wire sending out a message of ‘move along, nothing to see here’. The idea of cultivating gardens is ignored; odd when the fertility of the land, especially on the foothills of the mountains south of Jakarta, is considered.

The popularity of a well laid out garden is still there, witness the weekend and holiday crowds that fill the gardens at Bogor, Cibodas and Merkasari, but with the current mantra of build, build, build, we are some way from being offered a choice of spectacular gardens with a backdrop of a fine old house to enjoy.

In the absence of the real thing we are relegated to taking photographs of artificial floral displays set amid lush, fake, fountains with trophy fish at Changi Airport and shopping malls.