As Indonesia prepares to celebrate 66 years of independence it is an appropriate moment to turn the clock back 560 years to the middle of the 15th century,

before any European power had lain claim to parts of the archipelago, and marvel at the impact a dozen islands in the east of the archipelago and occupying no more than 240 square kilometres, have had on world history and cartography.

A dozen islands referred to are, of course, the fabled ‘Spice Islands’ of the Moluccas, the Holy Grail of the European Renaissance explorers and merchant adventurers; Bartolomeu Diaz, Vaco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, Francis Drake and even Christopher Columbus who, although sailing westward from Spain, believed firmly that his landfall in the Caribbean was part of the Asian continent and therefore close to the Spice Islands. The sought-after spices were clove, nutmeg, mace and pepper with all but the latter being confined to the Moluccas Islands, the only place on earth where the plants grew; clove trees in the rich volcanic soils of Ternate, Tidore, Machian, Bachian, Motir and Potterbackers and nutmeg trees in the equally fertile volcanic soils of Great Banda (Lontar), Neira, Run, Way and Rozengain. Pepper vines grew more widely in the archipelago but were mainly concentrated in the southern tip of Sumatra (present-day Lampung) and in Aceh.

The spice trade is an ancient one and 1,500 years before Vasco da Gama’s three small caravels reached India in 1497 via the Cape of Good Hope, the Romans were sending annual fleets of 120 ships on the round trip to India to collect spices from the Arab merchants who dominated the trade and who went to extraordinary lengths to keep the sources of the spices secret. Before the sea route to the Indies was opened at the end of the 15th century, spices reached Venice, the centre for their distribution in Europe, via various overland routes including the ‘Silk Road’, combined with short sea journeys across the Mediterranean once the Arab seafarers had carried the precious cargoes from the Far East to India and thence to the entrepôt ports of the Middle East such as Aden and Cairo. This well-established trading network persisted into 14th century and was only seriously challenged and eventually broken when the Portuguese reached the Moluccas in 1512, followed nearly a century later by the Dutch, and wrested control of the spice trade from the Arabs.

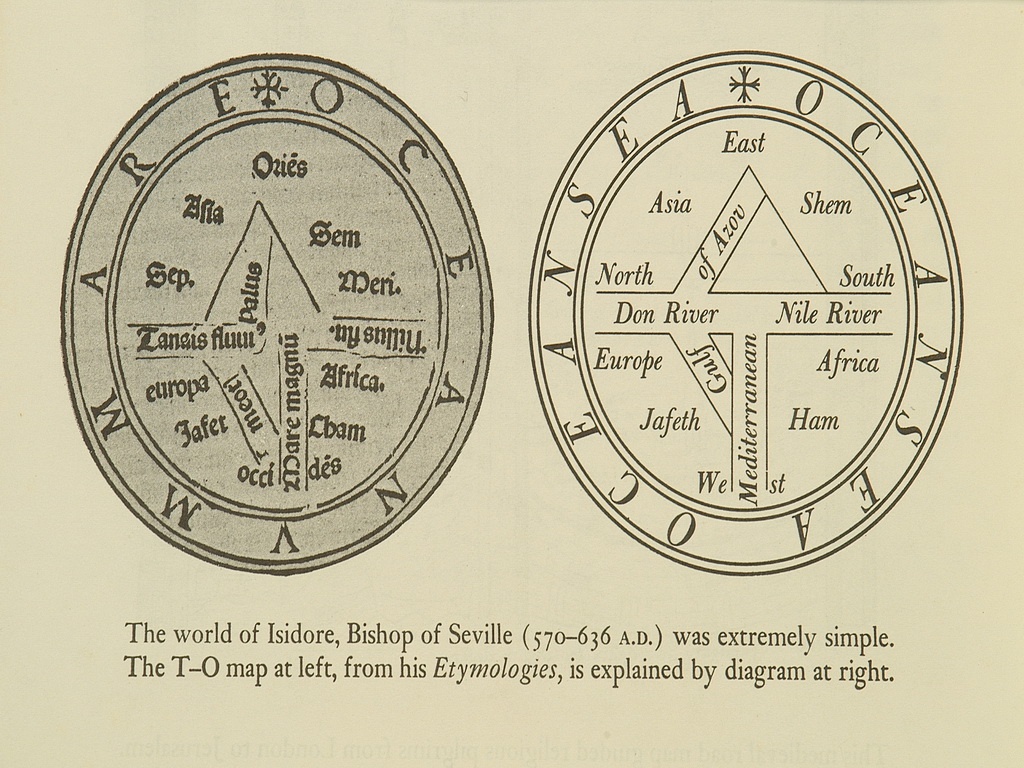

The probing voyages down the west coast of Africa by the Portuguese, first under the patronage of Prince Henry of Portugal, dubbed ‘The Navigator’, between 1418 and 1460, then by King Alfonso V between 1461 and 1481 and finally by King John II in whose reign Bartolomeu Diaz rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, set cartography and navigation on a scientific footing and began a revolution in ocean-going ship design, armament and marine logistics. For the previous 1,000 years what few maps there were tended to be based on church doctrine and were little more than diagrams and symbolic representations of the Earth’s continents centred on Jerusalem and showing paradise somewhere in the east; often referred to as T-O maps due to their configuration. As the medieval period drew to a close, more accurate and specific geographical information gleaned from various sources was added, together with colour, to such maps which were transformed into spectacular circular world maps or Mappa Mundi. One such example and the largest of its kind, made around 1290 by Richard of Haldingham, can be seen in Hereford Cathedral and in facsimile form in Bartele Gallery.

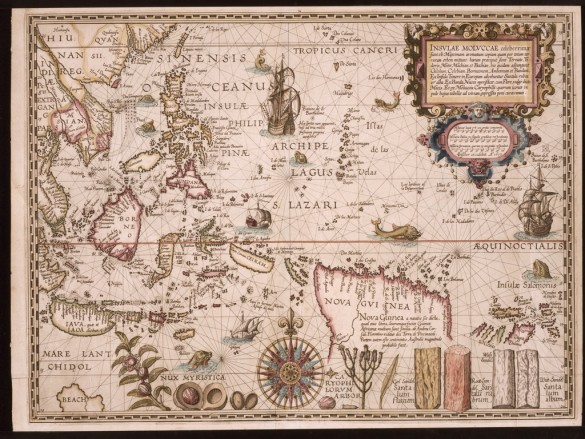

From 1512, the date the Portuguese ships reached the Moluccas, until the beginning of the 16th century, the Portuguese established a sea-borne empire stretching from Brazil to Macao. They refined the portolan chart, revived the spherical geometry of Claudius Ptolemy, the Greek founder of modern geodesy, to create detailed maps and charts of their empire, including South-east Asia and the Spice Islands, based on degrees of latitude and longitude, and in so doing began the process of unrolling the map of the world as we know it today. The zenith of Portuguese cartography of the Spice Islands is seen in the magnificent map Insulae Moluccae, compiled by the Flemish cartographer Petrus Plancius from Portuguese charts and travel itineraries (rutters) acquired in 1592. This beautiful and incredibly rare map, first published in 1598, shows Indonesia at a level of detail never before recorded and along its bottom margin contains engravings of the spices and other exotic commodities such as sandalwood that held the world in thrall for millennia. The appalling risks taken by seamen and merchants to reach the Spice Islands were balanced by the huge profits to be made from the spice trade where a kilogram of nutmeg would sell in Amsterdam in 1650 for nearly 900 times its purchase price in Banda.